After spending months in routes used by people in exile in the Balkans in 2022, Specto’s Eléonore Plé wanted to see with her own eyes the conditions of people from sub-Saharan Africa crossing into Tunisia with the hope of reaching Europe. “It is about the people, not numbers”, she says, in this interview about her project ‘Tunisia – Land of Passage’, supported by aidóni.

By Rogerio Simoes (edited by Méline Laffabry)

“This is the main subject of today, the main subject of this century.” This is how French journalist Eléonore Plé, the founder and director of Specto Media, explains why she chose to focus on migration in her most recent editorial projects – and she is not exaggerating. The movement of people, mostly from parts of the world facing violent conflicts, environmental disasters, and extreme poverty towards richer nations in the globe’s Northern Hemisphere, is defining the 21st century. In June 2023, the United Nations (UN) recorded 110 million displaced people worldwide. A new record…

Eléonore wanted to help change the way this momentous subject is portrayed and discussed, especially in the countries where the exiles arrive at the end of their journey. This is why she went to Tunisia, a country used by people of other African origins as a basis from which they try to reach Europe.

Her main goal was to tell human stories, to seek to understand the motivations behind the departures, and to shed light on the realities of the journey towards a hoped-for better future. “For me, it was a way of creating a new narrative, a new way to tell those stories”, she said in a conversation with aidóni. “There is a lot of disinformation, a lot of fear around this subject, and deshumanisation [of people in exile].”

If each migration story is unique and results from a multitude of factors, Eléonore explains that exploring this subject necessarily means investigating oppression, even if it manifests in different forms. “For me, it was a way of understanding oppression better. When you work with migration, you can cover sexual oppression, economic oppression, political oppression. That’s why there is a strong link between migration and human rights.”

“It’s about the people”

Eleonóre’s trip to Tunisia and its borders became Specto’s project “Tunisia, Land of Passage”, produced alongside aidóni. With so many numbers, graphics, and theories about migration from Africa already produced, promoted, and analysed, Eléonore focused on human stories.

“It’s about the people, not numbers, experts,” she says. “I wanted to go back to the basics, to tell people’s stories. We don’t usually hear those people. When people speak about migration, they always speak about politics, economics, numbers, but almost never listening to the people. When they do, it’s not in a good way, it’s through a narrative of crisis, catastrophe.” After people’s voices are properly heard, she says, the numbers, the context, and other views are added to complement the editorial content she produces around the subject.

Between November 2021 and March 2022, Eléonore travelled through several countries in the Bálkans to explore the conditions in which people were moving with the dream of a life in the European Union in their heads. The harsh conditions, particularly at the borders between countries such as Bulgaria and Turkey or Serbia and Hungary, made her want to discover more about the people who decide to attempt a journey to Europe despite the numerous dangers they encounter on their journey. Her attention then turned to Tunisia.

Indeed, this North African country serves as an informal gateway to Europe for many African exiles. Despite the increasing difficulty of crossing its borders, numerous sub-Saharan individuals take their chances with the aim of reaching the Mediterranean. The political and economic motivations behind the closure of Tunisian borders, as well as their financing, are more complex than they may seem.

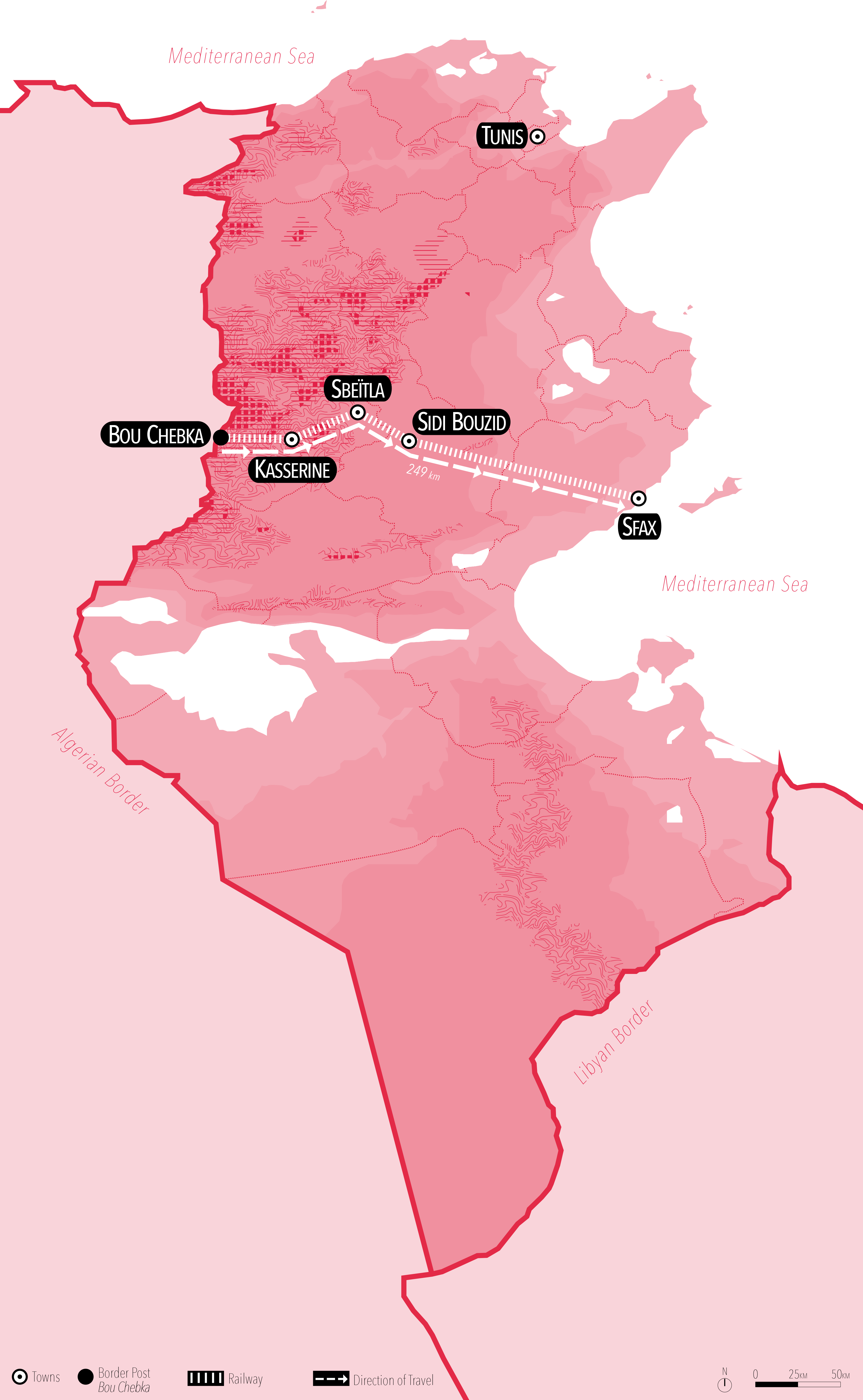

Her trip to Tunisia, in August 2023, included different stages of any migrant’s journey from that part of the world towards Europe. At the country’s border with Algeria, she witnessed the struggles, distress, and fatigue of those who had already travelled thousands of miles, from countries such as Burkina Faso, Cameroon and Sierra Leone, and had just managed to enter a new phase of their perilous journeys.

Silent questioning

With her friend and fixer Amin, whom she had met during her trip in the Balkans while he was working to document pushbacks at the border between Greece and Turkey, she first tried to get close to the border with Libya. That goal proved too dangerous, so she headed towards Algeria, focusing on that border instead – “a bit easier”, as Eléonore describes.

That was where she met the focus of her journalistic enterprise: the people dreaming of a life in Europe, escaping violence, persecution, and destitution. “It was very emotional, very hard, to meet people at the border with Algeria who had just crossed. Some of them had no shoes, water, women were alone with their babies, their children.” People refrained from speaking, opting to walk silently out of fear of patrols that could have sent them back across the border. The urgency of their survival made journalistic interaction challenging, requiring respect for their pace of escape.

“I’ve decided to shut up. Because, how could they speak? How could they give their testimony about what happened at the border when all they wanted was to drink something and then move on, and move on?” The connections and interactions between her and those people had to be carefully established, in order for trust to be secured and maintained throughout those conversations. “First thing was: they were scared of me. A few women told me, ‘I don’t know you, maybe you want something from me. I’ve just been raped by guards, I’ve just been sexually assaulted.’ They were very scared, so I thought I should just shut up and respecting their choice not to provide testimony.”

“I saw fear, survival, but also, with some of them, solidarity.” Eléonore recounts how a group of ten men ran to hide in the pistachio fields when they saw her approaching with Amin. They thought they were either the police or thieves. She had to approach them, explain that she was a French journalist, and show her face with the light of her phone for some of them to agree to talk to her.

“Step by step, one guy started to chat, then a second one. Two hours later, we were laughing, we were speaking about lots of things. Some were still quiet, just wanting to move forward, but with some it was funny.”

Helping create empathy

Those migrants’ stories, their conditions, and the hurdles they faced in their journey towards a better life – regardless of the reasons why they decided to start it in the first place – led Eléonore to a conclusion: she will have to continue producing stories around the subject because the issue will get worse before it gets, one day, a bit better.

“I cannot stop this work, that is what I’ve learned. Because this problem is huge and wont get any better. In my opinion, the way states are dealing with exiles will worsen. The policies of externalization and militarisation will deteriorate and lead to more and more tragedies and obstacles.” Upon her return to France, she wanted to quickly travel elsewhere to obtain other stories of migrants and their journeys. “For me, Tunisia was just the beginning.”

Eléonore describes herself as “pessimistic” when it comes to possible solutions that would either lead to either the accommodation of individuals in exile in more prosperous places, with dignity and hope, or the reduction or resolution of the causes that drove them to take to the road in the first place. “It’s not with a podcast series that we can change anything, I know.”

Works like her, nevertheless, can make a difference, even if on a quite small scale. One thing she would like to help create with the “Tunisia, A Land of Passage” series is “empathy”. “I just want to help create feelings in people’s hearts and put something new in their minds, so they can look at those who are on the move as human beings.” If that is achieved, Eléonore will be reassured that sitting down with people in exile to hear and record their stories is the right thing to do.

Pictures by Eléonore Plé, Tunisia, 2023

This article is part of the special series “Tunisia – Land of Passage”, produced by Specto Media and aidóni. Listen to the podcast here.

This multimedia series is produced by Specto Média.

Author: Eléonore Plé

Investigation and production: Eléonore Plé

Sound production: Norma Suzanne

Graphic identity: Amandine Beghoul and Baptiste Cazaubon

French version dubbing: Yamane Mousli

English version dubbing: Isobel Coen and Julian Cola

Editing: Hugo Sterchi and Norma Suzanne

Recording studio: Radio M’S

To discover the series in French, visit Specto Media

This multimedia series is produced in collaboration with aidóni for translation, and producing the articles and profiles.